The Genre That Melted Into Air:

Vaporwave’s Unstable Ideology and the Politics of Art in the Digital Age

A video frame centres on a pair of hands, steadily working their way through a dozen or so parcels. One by one, the goodies inside are revealed: a pastel anime girl on a white long-sleeve top, swim shorts branded with the SEGA logo, a candle shaped like a disfigured Roman bust. Out of shot, a voice cuts in, explaining that all these items are available at Vapor95, the “go-to” online store for clothing and accessories themed around ‘vaporwave’, a retro internet microgenre built from looped fragments of 80s/90s pop and lounge music.

While the video fits into the ‘unboxing’ category of YouTube, it is essentially a thirteen minute advertisement for Vapor95: long tracking shots of the products displayed in high definition are spliced alongside footage of them being unwrapped. If it wasn’t already obvious that the video wants you to check out the website, the unboxing is put on hold so that Vapor95’s URL can flash up on the screen in big letters. “LINK TO SHOP IN DESCRIPTION BELOW!” is the accompanying message, which the voice dutifully reads aloud.

Written in similarly arresting all-caps is the video’s misleading title: ‘SPENDING $300 ON VAPORWAVE STUFF’. ‘Pad Chennington’ (the username of the video’s author and owner of the aforementioned hands) hasn’t actually spent anything on these items. He puts it euphemistically as having “the opportunity to drop three hundred bucks” — they’re freebies gifted by Vapor95 with the understanding that his endorsement will attract customers from his 70,000-strong subscriber base. Referring to himself as the “vaporwave valedictorian”, Pad has amassed this impressive following over several years by uploading more than a hundred videos dedicated to discussions of the genre.

Unboxings aren’t a staple of my online viewing diet (there’s something uneasy about advertising that masquerades as entertainment) and while this one was undoubtedly a little heavy on the product placement, the format wasn’t exceptional. Businesses like Vapor95 hand out giveaways to popular content creators all the time under this model, and given YouTube’s volatile terms of service, brand deals have become a fact of life for those wanting to earn a living from the site. What caught my eye, is that a self-proclaimed expert hadn’t spotted any irony in commodifying a genre so commonly hailed as a consumerist critique.

At what point does a subculture die? That’s the question I’m asking myself as I sit, staring blankly at the screen. Since they emerge as diversions from the dominant culture, their assimilation into the corporate mainstream has historically functioned as their death knell. When Crass released ‘Punk Is Dead’ in ’78, Steve Ignorant sang: “Yes that’s right, punk is dead / It’s just another cheap product for the consumers’ head”. Commodification of a subculture and subcultural death go hand in hand; you need to be selling something in order to be a sellout.

Commodification in the name of mass appeal is not quite what I’m watching here, however. As successful as Pad’s YouTube channel is within the vaporwave community, it’s still niche. In the decade since it was first amalgamated from the anonymous bowels of the internet, vaporwave has continually flirted with the mainstream without ever quite going pop. Even if the name is unfamiliar, you’ll likely recognise its accompanying artwork from the several instances it has bubbled up to pop culture’s surface. Mic once described The Life Of Pablo’s album cover as having a “brutally simple vaporwave aesthetic”, whilst its influence elsewhere has been seen in the net-art behind Rihanna’s SNL performance of ‘Diamonds‘, the neon glow of Drake’s ‘Hotline Bling‘ music video, and the clunky computer graphics of MTV and Tumblr’s 2015 rebrandings.

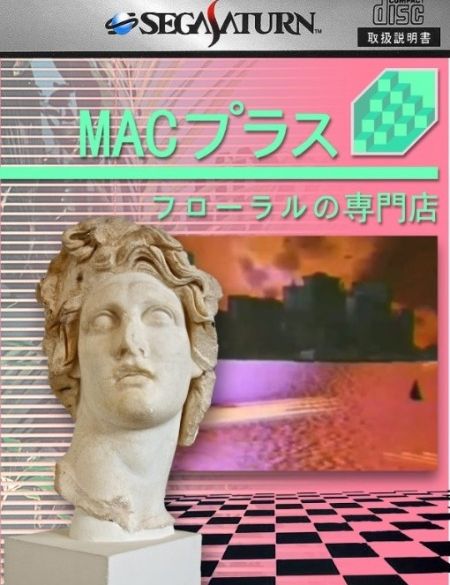

Vaporwave’s visual style was ripe for reintegration back into our collective consciousness since it was from those recesses that it had originally taken its inspiration. Like the consumer iconography it calls back to, vaporwave art is at once both omnivorous and unmistakable; corporate detritus left over from last century is reconstructed into heady collages of 3-D rendered imagery, obsolete electronic hardware, and looming cityscapes, with releases credited to fictitious conglomerates such as Saint Pepsi, New Dreams Ltd., and Luxury Elite. This hallucinatory mix of pixelated vistas, classical statues, and Japanese script might seem eclectic in isolation, but their relative consistency across releases (tied together by a trademark purple colour palette) ensures that there is a method to the madness.

Defining vaporwave’s sound is a little trickier. In the summer of 2010, Daniel Lopatin’s Eccojams Vol. 1 provided an initial template; vocal snippets from 80s pop were chopped and screwed into woozy, club non-anthems that induced you into a trance as often as they jolted you out of one. By imperfectly replicating songs of the past, Eccojams’ sonic and temporal indeterminacy left fertile ground for reinterpretation, and it wasn’t long before distinct variants started cropping up. French house, ambient, nu-disco, and trap have all found themselves subsumed into its amorphous production, and while vaporwave is often mistakenly credited as being the first entirely internet-based music genre, perhaps it’s a result of this malleability that it became the first to survive its teething period….

…Though not without its hitches. Unlike vaporwave’s now-defunct predecessors, such as ‘seapunk’ and ‘witch house’, checking for vaporwave’s vital signs proves not so clear cut since undergoing deaths and rebirths has become the signature feature of its short lifetime. In the ruthless arena of internet culture, where desperately short attention spans redefine zeitgeists as quickly as they define them, chronicling the exact dates of these demises can feel a little like drawing a line in quicksand.

The morbid slogan ‘vaporwave is dead’ first appeared in mid-2013 after pioneering artist Ramona Xavier announced what appeared to be her retirement from the genre. Antithetical to its message however, the intrigue behind the statement’s stark cynicism helped draw attention from outside the forums on Reddit and Last.fm that vaporwave had previously been confined to. In a tongue-in-cheek effort to ‘kill off’ the genre’s stagnating sound, prominent artist David Russo anonymously released Vaporwave Is Dead at the end of 2015, though in similar fashion to Xavier’s announcement, the album’s ominous title only piqued further interest. According to data from Google, it would take another year before web searches for the term ‘vaporwave’ started to decline.

Vaporwave is far from the first music genre to come attached to a ‘poseur’ discourse. But the extent that its community was fixated on invalidating its own existence — making ‘vaporwave is dead’ the genre’s default status — perhaps is owed to its anti-commercial associations.

Of all the ways we imagined The Communist Manifesto might persist in its cultural reach over the previous decade, what surely must be the most bizarre manifestation was its role in creating a folk etymology for a net-era music genre. Writing for Dummy in June 2012 during genre’s formative throes, Adam Harper pointed out that alongside its verbal similarity to ‘vapor-ware’ (advertised products designed to raise brand awareness without ever making it to market), the word ‘vaporwave’ was reminiscent of bourgeois capitalism’s ever-changing social conditions as described by Marx.

“Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones”, Marx wrote, “all that is solid melts into air”. Since demand for innovation in consumer goods is constant, so too is innovation in the production of those goods. This constant innovation destabilises the role of the industrial class, resulting in an uncertainty that ultimately hinders social mobility. The relevance to vaporwave, whose artwork unapologetically glamourised finance-sector skylines and the futures they promised in digital ephemera, was hardly out of place.

Harper wasn’t the first to see a satirical slant to the corporate muzak much of the genre sampled, nor was this his only interpretation. As easily as he called early vaporwave pioneers “sarcastic anti-capitalists revealing the lies and slippages of modern techno-culture”, so too were they the “willing facilitators” of said culture. But here an irresistible narrative began to take hold: a plucky band of bedroom-based producers united not by geographical convenience, but solely through their unwavering political idealism, were taking on global capitalism one free-to-download release at a time. Despite Harper’s insistence on vaporwave’s conflicting doctrines, in the space of a few lines an anti-capitalist reading had been codified into the genre’s definitive raison d’être.

Any hesitation over just how committed these musicians really were quickly became overshadowed by a vision of DIY digital punks. Harper’s fingerprints appear all over subsequent writing. In a feature on the neo-nazi subgenre ‘fashwave’ (‘fascism’ + ‘vaporwave’), Mic contributor Jack Smith IV recycled the same Marx quote, claiming that “many believe this is the origin of the term”. Less than eighteen months after Harper’s initial Dummy piece, Michelle Lhooq turned Harper’s retroactively-made ‘vaporwave/vaporware’ observation into canonical history, stating in a comment for VICE that the name was “a spoof of the term ‘vaporware’” (in reality, ‘vaporwave’ stuck after it was picked out by artist Robin Burnett from a cluster of Last.fm tags as the music evoked “fogged-out environments”). For Lhooq, vaporwave was unequivocally “punk” in that it was “driven by a subversive political objective: undermining the iron grip of global capitalism”. Her sentiment finds a spiritual successor in a 2016 Esquire article, in which we’re told that although vaporwave “might mimic the aesthetics of capitalism … it has more in common with punk. It’s political”.

Seen through these eyes, vaporwave ‘lived’ so long as there were artists to take aim at capitalist behemoths and listeners hungry for their dogma. Vaporwave’s online gatekeepers pronounced the genre ‘dead’ as soon as Rihanna reappropriated its aesthetics for her SNL ‘Diamonds’ performance in late 2012, but in truth, it’s not mainstream exposure alone that kills a subculture. Tempting though it may be to attribute the death of a subculture to a single watershed moment, efforts by big brands to capitalise on their burgeoning popularity are inevitable. A subculture dies when the very values that set it apart are compromised by its own community.

Determining their exact time of death proves impossible to pin down precisely because subcultures die when no-one is looking. Over-exposed under the public spotlight, it’s only a matter of time before ideological decay sets in. Recognisable features remain, but without the legitimacy of being an underground movement, their previous urgency wanes taking external interest with it. Wasting away, they slowly cross the threshold of collective memory. By the time someone remembers to check in on them, they find little more than a hollow copy. The final nail in a subculture’s coffin doesn’t come via a corporate buyout; you’ll know it’s dead when it’s rotting from the inside.

Holding a bandana up to the camera, Pad tells us he doesn’t ever plan on wearing it, he just wanted “one of everything … a taste of every little thing”. In his unboxing video’s sequel (in which the ante is upped to $500) we’re shown a sweatshirt with a vaporwave album cover printed in black and white. The original art is an eye-watering assault of cyan and hot pink, and Pad understandably prefers this monochrome version: “I don’t think I could ever see myself like seriously going out and wearing the actual Macintosh Plus album cover”. Except the next item he unwraps is an identical sweatshirt printed in the colours he just said he’d never go out in.

His reasoning? “I saw this on the site too and I said ‘why not pick one of these up’”, Pad admits, before unwrapping a t-shirt, some sweatpants, and a hoodie all with the same vibrant colour scheme, none of which it is clear he will ever put on. Under this business model, he’s been put in the strange position of selecting items based on a predetermined number value rather than by their use to him. Kanji lettering on a baseball cap is dismissed as “Japanese characters or Chinese characters, I’m not really sure” and we’re mistakenly told the female bust is “definitely a helios statue”, but should we really be surprised Pad isn’t bothered by details when half the reason he owns these products is so that they can be used to sell more products?

Dig a little deeper and discerning Pad’s position on commodifying vaporwave turns into its own rabbit hole. Throughout his video introduction to ‘mallsoft’ (a vaporwave subgenre named for its recreation of ambient sounds in shopping centres) released about a year before the unboxing, Pad envisions for us a stereotypical ’80s American mall. Emblazoned across a video montage of bustling escalators is the word ‘hyperconsumerism’, as Pad’s narration guides us through a vast imagined structure, its pristine walls gently echoing the sprinkle of faraway fountains, the air scented with cinnamon buns and buttery pretzels. Don’t be fooled by this consumerist honey-trap, “the persuading store displays” are fit to burst with an “over-abundance of goods we all thought we needed”.

The lilt in Pad’s voice seems to disapprove of the false value placed in commodities and the unsavoury methods used by corporate advertising, and what’s worse is that it sounds like we still live under these conditions, though “nowadays this experience has basically been distilled into a more practical form” with the internet. The transition from real to virtual plaza is seamless; a theory as to why vaporwave artists are so drawn to the aesthetics of 80s artifacts is that the consumer culture of Reagan’s America mirrors our contemporary obsession with the newest handheld technology. Yet even as he acknowledges this, Pad can’t help but find himself longing for “the grand exposure these commercial structures exuberated”. With an enticing pile of objects strewn around him, he is the persuading store display.

How does Pad reconcile this? “Vaporwave is consumerism to the fullest degree, and it is also anti-consumerism to the fullest degree”, he writes back when I ask him this question, “it all depends on how you want it to be for that moment in time”. To Pad, political themes in vaporwave aren’t a means to provide social commentary, they’re an aesthetic choice. “It’s fun to re-imagine and romanticise subjects like consumerism [and] extreme corporatism”, he elaborates, since their troubling economic implications don’t belong to the drudgery of our own world but a hyperreal dystopia. The listener is taken on a “complete trip to a setting”, protected from the harsh realities of labour exploitation, drastic wealth inequality, and monopolised markets by a stylised veil of fantasy escapism.

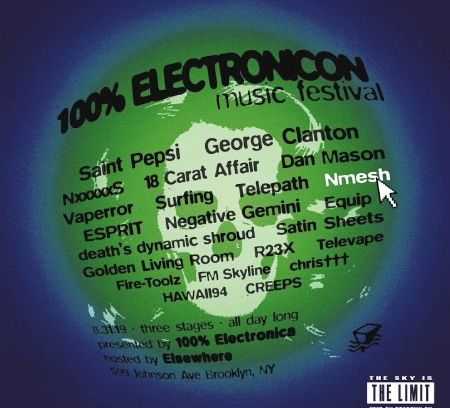

His response might seem frustratingly elusive, but Pad’s political apathy is the rule, not the exception. Last summer saw him make a guest DJ appearance at the first vaporwave music festival ‘100% ElectroniCON’, named after host George Clanton’s label 100% Electronica. Covering the event for Document, Nick Fulton thought it “a little ironic” that fans were encouraged to don their 100% Electronica-branded gear given the genre’s public romance with anti-consumerism. But when he puts this to Clanton, the notion is unceremoniously shut down. Clanton accuses “book-learning types” of commenting on vaporwave’s relationship to consumerism as merely a way to make “some of the more boring artists of the genre more interesting”, whilst for him and “the majority of listeners, it’s about the sound and the feeling”. He’s definitely right about that last part; if you were expecting the comment section under Pad’s unboxing video to have their teeth bared, think again. The closest they come to outrage is disaffected sarcasm, typed in the spaced out capitals typical of vaporwave art:

???????????????????????????????????????????? ???????? ???????? ???????????????????????? ????????????????????????????

Is this, then, what a dead subculture looks like: ideological core sloughed away, plastered over with a price tag? Underground music history would tell us as much; the merchandising of ‘cool’ relies on radical art movements being sterilised of their divisive politics, thus making them palatable for mainstream audiences. This template for assessing cultural history relies on the assumption that there is a distinct radical agenda to co-opt. But as a product of the web’s erratic cultural diaspora, vaporwave was never singular in its intentions.

Returning to Harper’s article for Dummy, the cracks in the genre’s fractured identity had always been showing. Later writers would come to mythologise Harper’s Marxist references to the point of being the genre’s ideological bedrock, but a quick glance up the page would have told you these speculations at vaporwave’s anti-corporate beginnings belonged to one of several contrasting interpretations. Frustrated with half-remembered versions of his ideas being regurgitated online, Harper took to his Tumblrwith a list titled ‘10 popular misconceptions about my original vaporwave article’. Numbers four and five read: “It said vaporwave was anti-capitalist”/“It said vaporwave was pro-capitalist”.

Harper had posited a tension between producers railing against late-stage capitalism’s systemic pitfalls and those “shivering with delight” at the prospect of societal decline. But under closer scrutiny, one of his article’s two interviewees refuses to fit comfortably into even these two categories, resembling something closer to a total disengagement from any political discourse than a “willing facilitator”. The first, Robin Burnett, was correctly identified as a “staunch anti-capitalist”, explicit that their repurposed corporate training video instrumentals reflected concerns with the idolisation of commodities. Curiously however, when Harper asked Ramona Xavier about the political implications of the corporate stock music she sampled, her answer was enigmatically ambivalent. She conceded her production technique was “sarcastic”, though the work itself was emphatically “sincere”. The “most effective social commentary”, she concluded, “is the one without dialogue”. She might not revel in the consumer culture Burnett was so preoccupied with resisting, but neither is she wholly opposed to it; Macintosh Plus, the artist whose album cover appeared branded on the merchandise in Pad Chennington’s $500 video, is one of Xavier’s many aliases.

It’s hard to imagine “staunch anti-capitalist” Robin Burnett having their own line of branded clothing, though to call Xavier a ‘pro-capitalist’ implies her work is self-consciously political, something to which she herself gives little indication.

Regardless of where Xavier sits on this spectrum, the similarity between some of her releases and Burnett’s, despite their ideological gulf, reveals a broader potential for the political intentions of vaporwave producers to be misread. Take this review of James Ferraro’s Far Side Virtual from late-2011, in which writer Brandon Soderberg looks at moments of hesitation in the album’s relentlessly peppy mood as evidence Ferraro is “subtly unveiling the horrors behind music”. Soderberg begins with Ferraro “star[ing] down at our contemporary world of the future … with an equal sense of dread and awe”, yet when Ferraro himself was asked by Harper a few months prior whether we should be afraid of the future, his response was more intrigued than fearful:

I’m at a coffee shop, co-oping in the shared pleasantness of other MacBook users via our united wi-fi provider. This safety zone is a glimpse into the future, a look into a small group of espresso drinkers who believe in a digital Utopia. We have crocs on, Alpha Generational babies in slick ethno slings. Human-like domesticated pets. Eco-friendly plastic cups. These people represent a determinism that is informed by commodities. But there is room to dream somehow. I definitely don’t fear them. I’m applauding them.

In his observation that the songs on Far Side Virtual sound “exactly the same as what they’re ostensibly parodying”, Soderberg inadvertently calls attention to the ease with which irony on the internet is either misidentified or just plain missed. Untethered to a physical scene and distributed in an environment saturated with (mis)information, it seems inevitable that whatever sarcastic political nuance there had been to certain early vaporwave releases was lost almost as soon as it crossed the digital plane. Its easily replicable and recognisable aesthetic meanwhile endures.

Does Harper agree with this theory? In part. “It wasn’t necessarily the internet that does this”, he tells me over Skype, “although I would say the internet increases the speed”. Harper points to vaporwave’s “inherent anonymousness” as to why it was so vulnerable to becoming decontextualised. Released by artists with oblique pseudonyms, exclusively as digital media devoid of intelligible lyrics or liner notes, “these albums just float around the internet”. He likens them to “a ship in a bottle”, floating its way into a new pair of hands halfway across the world. He’s right of course; even in cases where a producer’s intentions were politically radical, the subtle messaging in the ironic use of corporate aesthetics ensured that whether vaporwave was seen as “a cool-retro style” or a “complex commentary” was dependent on the listener.

But while there always exists potential for irony to be misconstrued, the internet allows for such a total separation between art and its context that irony becomes almost impossible to identify.

Vaporwave continues to be such an intriguing blueprint for the reception of net-era genres, because the internet provided both a platform for its anonymity and the instant proliferation necessary to destabilise its identity. Vaporwave doesn’t fit into a typical model of a radical art movement repossessed by the corporate mainstream, because the emerging gap between critical and fan-led discourse brought about by the internet has forced us to reassess what it means for a subculture to be considered ‘dead’. Vaporwave’s misinterpretations and divergent ideologies are perhaps a portent of things to come. When we have provided ourselves with a space to construct digital personas independent of a single identity, why should we expect our digitally-constructed music genres to be any more cohesive?